This supports Susan Nalezyty’s proposition that Girolama was important to the Accademia as a provider of printed images used as models for the students, who the academicians hoped to train in the style of the best masters.[5] However, she was scarcely the most visible of the intagliatori that Baglione mentions; in fact, he does not mention her. What did she alone add to the gallery of academicians that, like Baglione’s Vite, self-consciously plotted a history of the development of the arts in Rome?

By examining Parasole’s presence among the academicians through a close look at her known training, professional work, and associations, we place an unavoidably speculative notion of her ambitions and opportunities in a rapidly changing profession and social world into juxtaposition with conjecture about what the Accademia gained by writing into its history that particular portrait of a woman who carved images designed by others into woodblocks for printing.

Printmaking and the Progression of the Arts in Rome: The Interested Case of Girolama Parasole

Evelyn Lincoln

“The posthumous reputation of the artist needs care and tending…the sensitive executor is like a gardener, familiar with art’s ecology, tending the work that remains, balancing the compost of images, discourse and materials that generate the capacity for new readings…Our desire is not disinterested…” [1] —Caroline Jones

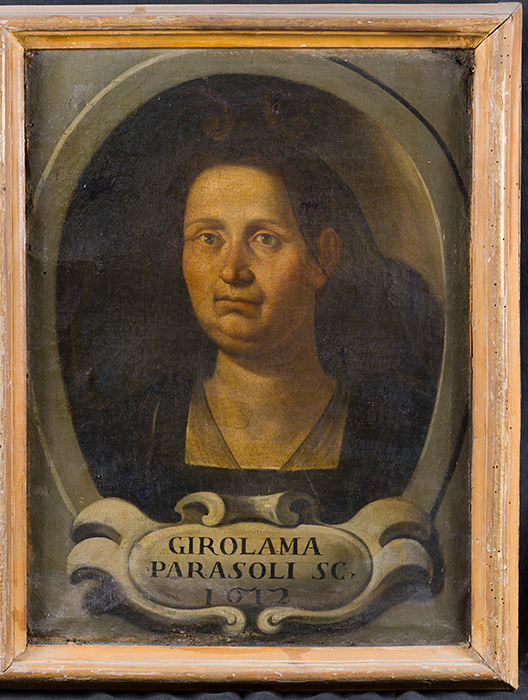

Girolama Cagnaccia Parasole (c. 1567–1622) interests us today as one of the few early modern women who left a historical record that allows us to partially retrace the circumstances of her professional life as a printmaker and, depending on how we define the word, as an artist. Her few signed prints, an anonymous portrait of her in the Accademia di San Luca, and a tiny amount of documentation of her everyday life, much of it inferential, can yield different and somewhat conflicting narratives. The questions we ask of her as a historical figure depend on the histories we wish to write.

In an article on what she terms the “artist-function,” Caroline Jones describes the historian’s responsibility in producing a coherent authorial figure from known works of art along with “the effects of inscriptions, texts and talk” that remain after the death of an artist, noting how different individuals can emerge from historical analysis.[2] Central to the question of the portrait of a particularly, perhaps purposefully, undistinguished-looking female artisan among the lace-collared, idealized, and perfectly posed likenesses of male academicians, is the question of who historians wish her to be. Chronologically, the first of these historians are the academicians who entered her portrait into the historical record of the Accademia. The second group is made up of historians who use that ostentatiously inclusive and disruptive act, as well as Girolama Parasole’s surviving artwork, to understand the formation of the arts, the development of printmaking as an art, and the participation of women in the arts through the opening that printmaking allowed. These two histories, we will see, might be at odds with each other.

Since the beginning of the 16th century, the authorial responsibilities involved in creating printed images were designated separately. The person who invented the image was identified on prints by the word invenit, the person who copied the invention onto a printing matrix by disegnavit, and the person who engraved it into copper or wood by sculpsit or incidit. The attribution of skill in disegno, which had bearing on who was understood to be an artist, was dispersed among categories privileged by Giorgio Vasari and subsequently at both the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in Florence and the Accademia di San Luca in Rome. Giovanni Baglione made a point of recognizing printmakers who were not necessarily inventors as practitioners of disegno. At the end of his Vite de’ pittori, scultori et architetti (1642), Baglione, who was principe of the Accademia di San Luca several times, added a short section on intagliatori that allowed someone who carved other artists’ inventions to be included in the Accademia’s conception of an artist.[3]

The fact that he included the Parasole family among his Vite was unusual, given that they worked primarily in book illustration and, with two notable exceptions by Girolama, did not make single-sheet prints. Baglione begins by defending the inclusion of printmakers among the artists:

good intagliatori in etching or engraving also understand disegno; and have a place among Painters, because with their sheets of paper they perpetuate the works of the most famous masters. And while their efforts sometimes fade in the public eye, they are admired, and one cannot deny that their sheets ennoble and enrich the Cities of the World. Also, some painters, in the end, have their works made into etchings or engravings, and as they were painters, they were also engravers. They can boast these virtues in common, and are equally praised.[4]

Fig. 1. Anonymous, Portrait of Girolama Parasole, before 1633, oil on canvas, Accademia di San Luca, Rome

The portrait of Girolama shows a clear-eyed new widow, a modestly veiled donna onesta, a working woman in simple, unadorned dress, presented to us without lace or jewels, unguarded, as if unaccustomed to posing or scrutiny, or perhaps stunned by her new situation (fig. 1). The painter seems familiar with the particularities of her face, and the circumstances of her life. There is a sense of vulnerability in its lack of pretention; she looks unaware of being studied. A devout Oratorian and active member of that congregation since its inception, Girolama worked for most of her life with her husband, Leonardo Parasole (d. 1612), and other members of her family carving images into boxwood blocks to illustrate an astonishing range of books published in Rome around the turn of the 17th century.[6] Illustrations in books, no matter their subject or genre, were resources for a varied and expanding image-using market that included the ambitious art students of the Accademia. The Parasole family provided woodblock illustrations for prestigious publications on New World plants; images in canonical liturgical books that required republishing after the Council of Trent; hagiographies and descriptions of martyrdom; visualizations of arcane iconography; and images for books in Arabic for the Medici Oriental Press. Portraits of clerics and rulers and images of the city created more opportunities for the family. It is likely that Girolama worked with her husband, her sister-in-law Isabella Parasole, and her brother-in-law Rosato Parasole on model books of lace patterns, which would have been the most notably original works of invention from this second iteration of the busy family workshop.

While Parasole is named and present in some surviving legal documents related to family matters and real estate that she owned in the city, her professional presence, and even her name, are confusing. In legal documents written in Latin, she appears as Hieronima Cagnaccia Parasole or a variation on that name. The monogram she used in the few cases where she signed woodcuts in illustrated books was “G.AP” with a tiny image of a woodcarver's knife, a matching pendant to her husband’s monogram, “LP” with a knife. Her two large, undated, single-sheet prints are signed with her name in Latin, Hieronima Parasole. The cartouche at the bottom of her Accademia portrait, which may have been painted later than the portrait itself, gives her name in Italian along with the date and her profession: “Girolama Parasoli, Sc./1612.”[7] We are looking at a portrayal of a sculptor in woodworking for the first time under her own name, as would be appropriate for widows.

Attempting to characterize Girolama’s talent, skills, and even her oeuvre puts us on unstable terrain. She never claimed to design the prints we know she carved. Indeed she worked in the space between the world of invention, increasingly represented at the Accademia di San Luca, and the world of production and circulation that took place in the printshops and bookshops at the center of Rome. No contracts or agreements of association have yet been discovered that help us to understand the conduct of Girolama’s professional life, although documents regarding that of her husband and brother-in-law do exist.

Women transacting business in Rome during this period required a mundualdus to enter into a contract. This male relative or family friend negotiated contractual terms and “provided a means of dealing with those potentially dysfunctional moments in the structure of male dominance when women entered the public arena.”[8] For this reason, when trying to piece together the professional life of a Roman woman from this period, it is necessary to interpret sources in light of social and family relations to understand what was socially and legally probable. Surviving materials for this include a notarial document from the beginning of Girolama’s career as a carver of woodblocks to illustrate books, and Baglione’s entry in a canonical work of the literature of art published two decades after her death. Since they bookend a discussion of Girolama Parasole’s career and reputation, we could begin by reading them together.

The document from the beginning of Girolama and Leonardo’s book-illustrating career frees Leonardo from association with a family workshop that practiced the “arte di zoccholi.”[9] It was contracted in 1585 at the death of his father, who arrived in Rome from Sant’Angelo in Visso in Norcia around 1572, and established a workshop for carving wooden clogs in the printing district.[10] The document releasing Leonardo from the family business shows that four Parasole sons worked together, each specializing in tasks necessary to run a shop that produced wooden shoes as well as small drums, tambourines, and small wooden caskets. While two brothers carved and would continue to carve the hardwood shoes, boxes, toys, and tambourines that were the shop’s mainstay, Rosato painted them with decorations and Leonardo carved woodblocks to print images that decorated them. The agreement shows that Leonardo had already begun working on his own, carving botanical images by an unknown designer for an herbal by the papal physician, Castore Durante.[11] Leonardo’s wife is mentioned but not named in the document, which shows that her dowry had been invested in the running of the shop, as had the dowry of another brother’s deceased wife, and the couple was allowed to extract those funds from the family association along with the paper, blocks, and prints related to the herbal. From the beginning of their Roman residency, the model for the Parasoles’ social and economic life was the family workshop, in which both men and women of an extended family shared work and financial resources. It is important to conceptualize Girolama Parasole’s formation as a sculptor in that structure, where she contributed her skills as a woodblock carver to a diversified family enterprise.

The second central, if convoluted, document is full of errors but sheds light on the arc of Girolama’s professional life and reputation: Baglione’s entry that included the Parasole family among biographies of noteworthy Roman artists.

We saw that the case for considering printmakers as artists rested on their expertise in disegno, and their role in making the works of the great(er) masters known to the wider world. Baglione draws painters and printmakers closer together by mentioning that some painters not only had their work made into prints, but perhaps made prints themselves. Although etchers and engravers in copper were the more prestigious printmakers, Baglione showed an unusual interest in woodblock cutting, providing an extended description of that craft in the life of the little-known Giovan Giorgio Nuvolstella. An active member of the Compagnia di San Giuseppe di Terrasanta from 1600 until his death in 1643, Baglione had personally associated with a wider variety of people involved with the arts—battilori (goldbeaters), intagliatori (engravers, carvers), librari (book and print sellers), and musici (musicians)—than he would have encountered at meetings of the Accademia, where he was equally deeply engaged.[12] The Compagnia admitted women as courtesy members, so he knew of the artist wives of other confratelli, although it is unclear if he ever met them. It is clear, however, that he did not know all the members of the Parasole family, none of whom appear in the confraternity’s rosters. He would have met Giovanni Battista Raimondi, the renowned Arabist who ran the Medici Oriental Press, with whom Leonardo worked closely in the last decades of his life.[13] Raimondi, who was deeply mourned by the confratelli at his death, was a friend of Girolama and Leonardo as well as an employer, and stood as godfather at the baptism of their daughter in 1589.[14] In a few short paragraphs, Baglione not only provided the single notice of the Parasole family in the early modern literature on art, but also scrambled their relationships to each other in a way that deeply misrepresented the character of their work, and their identities, for centuries to come.[15] But this confusion is productive for understanding Girolama Parasole’s conception of her work.

What can we learn about Girolama from Baglione’s account, in which he never mentions her? Toward the end of the previous vita, he tells us that some of Giovanni Maggi’s works had been made into woodblock prints by Paul Maupin, and probably knowing that Maupin and Leonardo Parasole had worked together, Baglione uses this as a bridge to the Vita di Lionardo, Isabella, e Bernardino Parasoli. These family members, whom he believes to be relevant to the progression of the arts of intaglio, are discussed as a group in his chapter on printmakers, even though Bernardino worked solely as a painter. Baglione writes: “Having mentioned wood carvings, I now present to memory Leonardo Parasole, Norcino, whose works were made in wood, who gained praise because in fact woodcutting is more dangerous and difficult than intaglio in copper.” He begins with the early herbal, noting that Durante had been the physician of Sixtus V. He says that Leonardo’s images were often supplied by Antonio Tempesta, including the pictures for the Arabic Gospels printed at the Medici Oriental Press, with special praise for its scholarly director Raimondi, the “grandissimo Letterato” who was so honored at his death by the artist’s confraternity. He writes that Leonardo’s son, Bernardino, had studied with the Cavalier d’Arpino, and while citing the frescoes he “colored with his own hand” in San Rocco, he can only say that he had died young, and “great things were hoped from him.”[16]

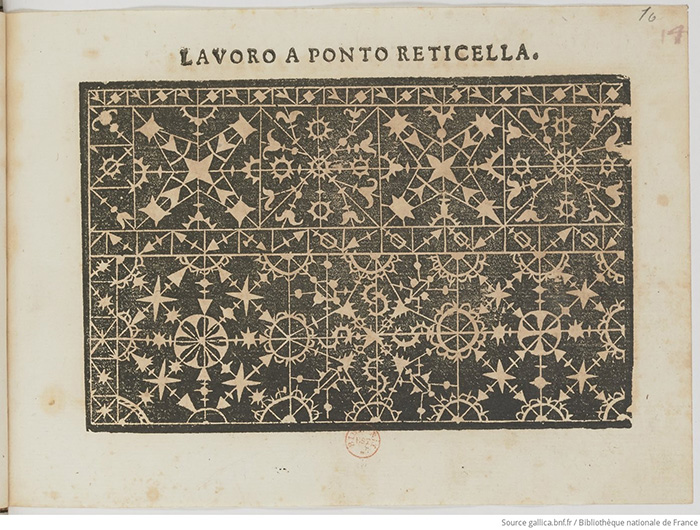

Fig. 2. Isabella Parasole, “Lavoro a ponto reticella,” in Specchio delle Virtuose Donne, dove si vedono bellissimi lavori di punto in aria, reticella, di maglia, & piombini, disegnata da Isabetta Catanea Parasole (Rome, 1595), n.p., Bibliothèque nationale de France

In this brief notice, Baglione collapses the sisters-in-law Isabella and Girolama under the name of Isabella. The women were probably known to him only through hearsay, and only Isabella’s name had ever appeared in print. Isabella Catanea Parasole, whom he mistakenly takes to be Leonardo’s wife and mother of his youngest son Bernardino, was the second wife of Leonardo’s painter brother Rosato. She was one of many marriageable young women in danger of falling into prostitution who, under the modern initiatives of Catholic reform, had been rescued from that life and brought to the Augustinian convent of Santa Caterina dei Funari, where girls were taught needlework and provided with dowries.[17] Rosato applied to the convent to marry Isabella in 1593, understanding the strength of the market for inventive ornamental patterns and the value of a well-educated, talented, industrious, and likely beautiful wife. Baglione seems to be completely unfamiliar with Leonardo’s actual wife. As Leonardo was the son of a shoemaker, Girolama was the daughter of a hatmaker, also originally from Visso.[18] Rosato left the family workshop the year after Leonardo to work as a mosaicist and decorative painter.[19] He earned a living in decorative wall painting, making ephemeral decorations for festivals and, from 1602, as a mosaicist for the interior dome of Saint Peter’s.[20] Although Rosato participated in at least some of the meetings of the Accademia di San Luca, Baglione never mentions him. However, he was the motivating force behind the first gorgeously illustrated model book of lace designs, printed in intricate white geometric patterns against a black background, that carried the name of his wife Isabella as the author (fig. 2). Appearing in 1595, it bore the graceful title Specchio delle Virtuose Donne, printed “ad’istantia di Rosato Parasole.”[21] Its long and appropriately courteous full-page dedication to the Duchess of Sermoneta shows that the new author was aware of the style and importance of the convention of placing a dedication at the beginning of a book.

It is most likely that the several ultimately famous lace pattern books authored by Isabella were designed, carved, and printed by members of the family and their associates working together. The Augustinian convent in which Isabella was taught specialized in training girls in the lucrative lace design that would make them useful to any artisanal family’s economy, but there is no reason to assume that they were taught how to carve hard and dense boxwood with intricate patterns, something Baglione makes a point of saying is dangerous and difficult. The tiny white triangles and circles that make up the lace patterns are cut away from the surface of the block with small, sharp blades. Baglione wrote in his vita of Nuvolstella:

The part that is not needed is excised, and the other, which is used, which remains there like a bas-relief, shows the images and represents stories; and the instrument for doing this is iron, which the Artisan handles to cut the work, and as he diminishes the material, the form grows, and the whole receives its perfection from the absence of these parts.[22]

Baglione says that Nuvolstella assisted Isabella in carving botanical images for Federico Cesi when she had trouble completing them. We know that it was Girolama who carved the botanical images, but Baglione’s confusion helps us understand how intertwined the work of the two women would have been as they combined their skills to produce pattern books, explaining the invisibility of Girolama’s unsigned but essential contribution to the projects.

Fig. 3. Ludovico Curione, Il modo di scrivere le cancellaresche corsive et altre maniere di lettere di Lodovico Curione. Intagliato in legno per Leonardo Parasole, Libro Primo (Rome, 1586), n.p., Biblioteca Archiginnasio Bologna

The year Rosato left the family workshop, Leonardo contracted with the publishers of the herbal to carve, print, and sell a model book of intricate calligraphy by one of the top writing masters of the period, Ludovico Curione.[23] Curione’s dedication to Cardinal d’Este could easily have been the model for Isabella’s courteous dedication in her model book almost ten years later. Unusually in a printed handwriting book, some calligraphy pages are rendered in white against a black background (fig. 3). The pages, carved seven years before Isabella joined the family, were framed with twirling flourishes in imitation of tapering and swelling pen lines, and the white-on-black imagery developed for these pages continued to be a feature of Parasole print design. A picture begins to emerge of a family of woodblock carvers and decorators with connections to illustrated book printing, as well as to papal and aristocratic circles.

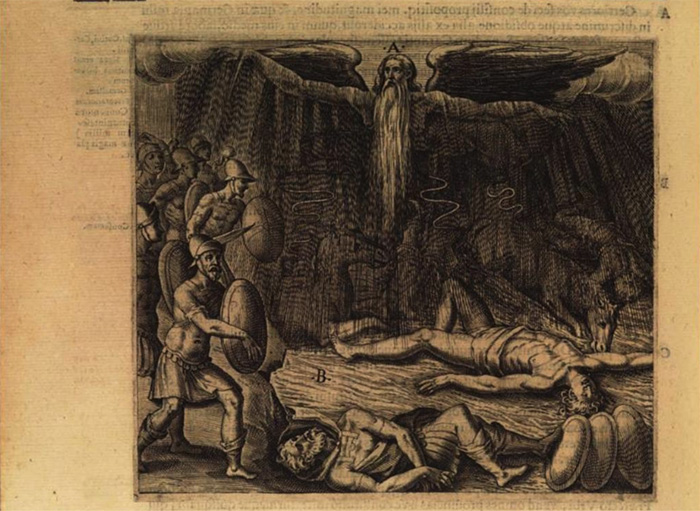

Fig. 4. Girolama Parasole, “Giove Pluvio,” from Cesare Baronio, Annales Ecclesiastici (Rome, 1594), 2:209, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

Inventories of their property made upon the deaths of Leonardo (d. 1612) and Girolama (d. 1622) show that there was no printing press in their home, only a worktable for cutting woodblocks. They do not seem to have owned a studio or workshop apart from their house across from the Trevi Fountain. Throughout their professional lives, they worked as image providers for associates like the printer Fachetti and the Oratorian publisher Jacopo Tornieri. It would have been in keeping with the family’s conception of a workshop for the two sisters-in-law to have worked together during the years when both of them were raising their many children. Girolama could expertly carve intricate images for botanical illustration as well as swirling, narrowly cut calligraphic tendrils that could survive the printing press, while Isabella knew how to invent and draw lace designs that visually incorporated and deconstructed floral and vine-like imagery.[24] Leonardo was an experienced advisor for creating printed model books and seeing publications through the maze of contracts, legal associations, finances, and official clearances they entailed, and Rosato’s experience as a decorative painter meant that he understood that patterns advertised for lace-making were equally useful to the work of wall painters, embroiderers, portrait painters, and even gardeners. The lively, courteous address in Isabella’s dedication to an actual or aspirational patron likely transcended the comportment of clog-makers and similar artisans, offering a window onto the education and social class of the convent’s wards and the patronage devout noblewomen practiced at religious houses for girls.[25] In this way, Rosato’s marriage to Isabella doubled the number of talented women in the family, bringing new skills and manners to the woodcarvers and broadening their production in the model book sector.

Fig. 5. “Giove Pluvio,” in Cesare Baronio, Annales Ecclesiastici (Rome, 1590), 2:198, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

All of Isabella’s pattern books bore unadorned title pages except for the last one, Teatro delle Nobili et Virtuose Donne (1616), which featured an elaborate ornamental frontispiece engraved by academician and fellow printmaker Francesco Villamena. This is the work of hers that Baglione cited in his vita. As Leonardo is burnished by association with Antonio Tempesta, and Bernardino with Giuseppe Cesari, Isabella is linked with the skillful male woodcarver Giovan Giorgio Nuvolstella and the academician Francesco Villamena. The somewhat thin story of Parasole artistic accomplishment that emerges is strengthened by framing it in a garland of praiseworthy popes, significant physicians, renowned scholars, and major participants at the Accademia di San Luca.

We have bracketed a description of Girolama’s career and her fame, such as it was, between two primary sources, neither of which actually name her. The instances of her signed work constitute a very short list. Three books include woodcut illustrations bearing her monogram:

1. Dialoghi…intorno alle medaglie inscrittioni et altre antichità, 1592.[26] The book is illustrated throughout with unsigned images of coins, including the inscriptions, which are the subject of the book. Only four images are signed, bearing the monograms of Girolama (under an image of the Arch of Titus), Leonardo, and Paul Maupin. The monogrammed full-page woodcuts show inscription-bearing Roman arches in an urban setting. Unlike the images of coins, they demonstrate the use of perspective, shading and atmospheric effects, architectural ornament, and figures. No inventor for these images is named, although some are clearly copies of well-known prints by Nicolas Beatrizet and others.

2. De SS. martyrvm crvciatibvs, 1594. This is a smaller-format Latin version, with woodcuts designed by Giovanni Guerra, of an Italian volume illustrated with etchings by Antonio Tempesta of tortures and martyrdoms of Catholic saints.[27]

Fig. 6. The Rain Miracle in the Territory of the Quadi, detail from the Column of Marcus Aurelius, c. 193 CE, marble carving

3. Annales Ecclestiastici, 1594. Most images in these volumes are of coins, as in Antonio Agustín’s dialogue, none of which are signed, but the publisher’s records show that Leonardo was paid a scudo apiece for images of coins during this period. He also received eight scudi in payment for a woodcut of Giove Pluvio, inspired by a famous scene on the column of Marcus Aurelius, that bears Girolama’s monogram.[28] Although it could be assumed, this provides evidence that contracts for Girolama’s work were enacted in Leonardo’s name.[29] The image, small enough to have been cut from the boxwood that was a specialty of the family, differs completely from an earlier version of the same volume printed in 1590 that was deemed unsatisfactory (figs. 4–6). Capitalizing on her skill in cutting dramatic white forms snaking across dark backgrounds, Girolama emphasizes the thunder and lightning that accompany the god, whose miraculous appearance brings life-giving rain. She skillfully works chiaroscuro effects into the image so that there is a sense of depth in the shadow behind the god, from which soldiers and horses tumble to their deaths. In the foreground, a pathetic figure lifted from ancient Niobid or Amazonomachy reliefs, perhaps by way of printed battle scenes like Marco Dente’s, lies crumpled and foreshortened in the swirling water, his head resting against one bent arm (fig. 7).[30]

Last, and possibly most important in thinking about the possible significance of her practice to Girolama’s Accademia portrait, are two large, ambitious, but undated narrative single-sheet woodcuts. The woodcuts, one biblical and one mythological, are both full of figures and made after drawings by Antonio Tempesta. Both are signed with Girolama’s full name instead of a monogram:

1. The Last Judgment, at lower left: HIER[onim].A P[arasol].E INC[idit]. /A[ntonio]TE[mpesta] (fig. 8).[31]

2. Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs, center bottom: HIERONIMA PARASOLIA INCID.; at lower right: ANTO. TEMPEST. Inven. (fig. 9).[32]

Fig. 7. Marco Dente after Raphael, Battle scene in a landscape with soldiers on horseback and several fallen men, another group of riders in the background, c. 1520, engraving, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959, 59.570.277

Both prints are much larger than the small boxwood blocks Girolama was accustomed to carving, which fit into printers’ frames among the text characters. These are slightly smaller than a sheet of foglio imperiale, and although the few surviving impressions of both prints are cropped close to the image, it is possible to see that there was originally a black border printed around them.[33] The size of Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs may be partly responsible for the boldness of its execution, which is difficult to notice properly for the unevenness of the ink distribution over such an expanse of image. The dramatic battle scene features sword-wielding centaurs and mounted soldiers; at the center bottom, over a banner unfurling to proclaim the Latin version of Girolama’s name, a defeated centaur lies crumpled on the ground, his head buried in his folded arm. The melee of men and horses is pure Tempesta, and Girolama has included his name rather proudly as inventor of the image on the strap of a buckler littering the foreground on the right.

Fig. 8. Girolama Parasole after Antonio Tempesta, The Last Judgment, n.d., woodblock print, Gabinetto dei disegni e delle stampe “Angelo Davoli,” Biblioteca Panizzi

There is so much still to know about this woodcut, as remarkable for its obvious ambition as a large, multi-figural battle scene as for having been carved by a woman who signed it front and center, in a gleeful visual proclamation of her role as its carver. While there is no date on the image, the full signature most likely means that Girolama was working alone, after the death of her husband. As a widow in Rome, she could move freely among the protective community of male artists and writers who had provided images for her and her husband to carve, and who had stood as godfathers and employers to their children. Perhaps she had taken note of the high value of her work on the image of Giove Pluvio, and felt confident enough to try printmaking in a different milieu—that of the artist—which would have offered new opportunities for intagliatori who, it was argued, should be considered as practitioners of disegno. The notice of her death in parish records intriguingly calls her a “sculptress and painter.”[34] But what did her presence in the form of a portrait add to the intentional history of the Accademia di San Luca and its narrative of the development of the arts in Rome? What was the role model her portrait provided for artists to follow?

Fig. 9. Girolama Parasole after Antonio Tempesta, Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs, n.d., woodblock print, The Art Institute of Chicago, The Amanda S. Johnson and Marion J. Livingston Fund, 1999.684

When paired with the portrait of Sofonisba Anguissola, which we now know was not a likeness but adequately represented the Accademia’s idea of her, we can imagine how these two images of women represented types and role models for artists (fig. 10). The presumptive portrait of Sofonisba as a court lady—with lace ruff, careful coiffure, and pearl earrings—could show a lady-in-waiting, as she was at the Spanish court, a milieu in which a woman could reasonably conduct herself as a painter, a type of artist not otherwise represented among the academic portraits. In contrast, the disturbingly plain portrait of Girolama shows us a devout artisan operating in her own name as a widow, dutifully carrying on a family profession as many widows did in the book printing business. Girolama’s reputation as a committed Christian, her work for the Vatican physician, or for Cardinal Cesare Baronio, as well as her possible presence in the many unsigned woodcuts for liturgical volumes organized and published by her husband at the turn of the century, made her an unusual symbol of the good that printed images could do in the world that the church was fashioning with the help of the devout populace of Christendom after the Council of Trent.[35] When portraits of women were included in series of uomini illustri, they were often presented as mythological or biblical characters, types as compared to the recognizable, time-bound men they accompanied. According to Gabriele Paleotti, who helpfully reminds us that it is important to distinguish between the act of making a portrait and the uses made of it afterward, portraits were supposed to portray “persons whose moral goodness or Christian sanctity may act as incentive to others to practice the virtues.”[36] A variety of portraits allowed students to parse the possible forms of greatness an artist might embody. Girolama’s portrait certainly adds a dimension to the Accademia’s notions of artistic women, however narrowly it may represent the actual working life, or ultimately unknowable aspirations, of the particular woman.

Fig. 10. Anonymous, Portrait of Sofonisba Anguissola, before 1633, oil on canvas, Accademia di San Luca, Rome

Baglione’s error points us to the community structures in which Girolama lived and worked, showing how anachronistic it is to assume that her portrait among the academicians meant that she took part in the art world in the same way as the academic artists with whom she actually worked closely: Antonio Tempesta, Francesco Villamena, Cristoforo Roncalli, and Giuseppe Cesari, for example, were particularly close to her and her family. A chronicle of her life and works, and of the few signed images that give us a sense of her partnership in a family workshop as well as her role in producing the picture atlas of early modern Roman intellectual life, cannot yield a coherent narrative about the Accademia’s portrait. Perhaps the most unusual aspect of the painted portrait of Girolama Parasole among those of the academicians is that it asks us to think more open-mindedly about the definition of, conduct of, and opportunities for printmakers in Rome during the period of Catholic reform, opportunities that the new Accademia found it helpful, up to a point, to embrace.

Notes

[1] Caroline Jones, “The Artist-Function and Posthumous Art History,” Art Journal 76, no. 1 (Spring 2017): 144–145.

[2] Jones 2017, 145, discussing the perceived coherence of the “posthumous author-function” created by historians.

[3] Giovanni Baglione, Le vite de’ pittori, scultori et architetti. Dal pontificato di Gregorio XIII del 1572. In fino a’ tempi di Papa Urbano Ottavo nel 1642 (Rome, 1642). On Baglione’s biographies of the printmakers, see Giovanni Maria Fara’s edition of Intagliatori (Pisa, 2016). Fara shows that Baglione used Giulio Mancini’s Considerazioni sulla pitture (section V, part 1) for information on many of these biographies. Those that do not appear in Mancini and seem to be Baglione’s invention include: Camillo Graffico, Raffaello Guidi, Giovanni Maggi, Giovan Giorgio Nuvolstella, and the Parasole family.

[4] Baglione 1642, 387: “Sogliono, ò Signor mio, esser’anche intendenti di disegno I buoni Intagliatori di acqua forte, o di bulino. E però tra Dipintori possono havere il luogo, poiche con le loro carte fanno perpetue l’opere de’ piu famosi maestri. Et benche le fatiche loro al cospetto del publico non sempre sieno stabile, e si mirino, pure non si puo negare, che li lor fogli non nobilitono, & arrichiscano le Città del Mondo. Anzi alcuni Artefici di Pittura, in fin essi hanno d’acquaforte, o di bulino le proprie opere intagliare, e come erano Pittori, così anche Intagliatori furono, & in loro queste Virtù hebbero commune il vanto, et indistinta la lode.”

[5] See Susan Nalezyty, “Girolama Parasole among the ‘Illustrious’ in the Portrait Collection at the Accademia di San Luca,” The History of the Accademia di San Luca, c. 1590–1635: Documents from the Archivio di Stato di Roma.

[6] For an overview of the Parasole family, see Evelyn Lincoln, “The Parasole Family Enterprise and Book Illustration at the Medici Press,” in The Medici Oriental Press: Knowledge and Cultural Transfer around 1600, ed. Eckhard Leuschner and Gerhard Wolf (Florence, 2022), 110–118.

[7] Marco Pupillo, “Gli incisori di Baronio. Il maestro ‘MGF,’ Philippe Thomassin, Leonardo e Girolama Parasole (con una nota su Isabella/Isabetta/Elisabetto Parasole),” in Baronio e le sue fonti, ed. Luigi Gulia (Sora, 2009), 845.

[8] Thomas Kuehn, Law, Family, and Women: Toward a Legal Anthropology of Renaissance Italy (Chicago, 1991), 237. For the Roman adoption of the Florentine custom, see Simona Feci, Christiane Klapisch-Zuber, Didier Lett, and Marian Rothstein, “Women’s Mobility, Rights, and Citizenship in Medieval and Early Modern Italy,” in “Gender and the Citizen,” Clio. Women, Gender, History, no. 43 (2016): 48–72.

[9] Document substantially published in Gian Ludovico Masetti Zannini, Stampatori e Librai a Roma nella seconda metà del Cinquecento (Rome, 1980), 279–280.

[10] The date of the family’s arrival in Rome is calculated from Leonardo’s deposition at the canonization trial of Filippo Neri on December 12, 1598. Testimony in Giovanni Incisa della Rocchetta and Nello Vian, eds., Il primo processo per San Filipo Neri (Vatican City, 1958), 2:212–214.

[11] Herbario Nuovo di Castore Durante (Rome, 1585).

[12] Vitaliano Tiberia, “Attività e ‘eredità’ di Giovanni Baglione per la Compagnia di San Giuseppe di Terrasanta,” in Studi sul Barocco romano. Scritti in onore di Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco (Milan, 2004), 35–38; J. A. F. Orbaan, “Virtuosi al Pantheon,” Repertorium für Kunstwissenschaft 37 (1915): 17–52, for lists of women affiliated with the sodality.

[13] Evangelium Iesu Christi quemadmodum scripsit Mar Mattheus unus ex duodecim discipulis eius (Rome, 1590), with a bilingual Arabic-Latin edition in 1591. See Caren Reimann, Die Arabischen Evangelien der Typographia Medicea, Buchhandel un Buchillustration in Rom un 1600 (Berlin, 2021).

[14] Orbaan 1915, 40–41; Pupillo 2009, 844.

[15] The documentation that disambiguated the relationships of the family members is published in Pupillo 2009.

[16] Bernardino was still alive and was named “unico figlio et herede” by the court when Girolama died intestate in 1622.

[17] Pupillo 2009, 847–848; Rose Marie San Juan, Rome: A City Out of Print (Minneapolis, 2001), 95–128; Alessandra Franco, “The Conservatorio di Santa Caterina della Rosa: Sheltering and Educating Women in Early Modern Rome” (PhD diss., Brown University, 2015).

[18] I am grateful to Tom and Libby Cohen for their help in confirming the definition of “capillarius.”

[19] ASR 30 Not Cap. uff. 16, ASR 30 Not Cap., Atti Bernardino Pascasius, f. 193r: 21 febraro 1586. In 1593 Rosato is documented as painting a decoration on a wall for a client, May 18–19, 1593, Atti Tino, v. 14, cc. 383r–384r.

[20] Lincoln 2022, 101.

[21] Isabetta Parasole, Specchio delle Virtuose Donne, dove si vedono bellissimi lavori di punto in aria, reticella, di maglia, & piombini, disegnata da Isabetta Catanea Parasole (Rome, 1595).

[22] Baglione 1642, 396, in the section on Intagliatori: “Et hora l’età nostra mirasi ne’legni figurar gl’intagli delle sue opere. Cava è la parte, che non serve; e l’altra, che serve, restandovi a guisa di basso rilievo, mostra l’imagini, e rappresenta l’historie; e lo stromento a ciò fare è un ferro, che dall’Artefice maneggiato co’l taglio opera, e mentre sminuisce la materia, cresce la forma, e dal mancamento delle parti riceve la perfettione il tutto.”

[23] Il modo di scrivere le cancelleresche et altre maniere di lettere di Lodovico Curione. Intagliato in legno per Leonardo Parasole, Libro Primo (Rome, 1586).

[24] Pupillo 2009, 849, suggested that another family member probably carved the lace manuals, as the working and designing of lace was the specialty taught at Augustinian convents.

[25] Pupillo 2009, 848, suggests that Isabella herself may have had a noble parent.

[26] Antonio Agustín, Dialoghi di Don Antonio Agostini arcivescovo di Tarracona intorno alle medaglie inscrittioni et altre antichità (Rome, 1592), 124. Leonardo’s monogram appears on page 126.

[27] Antonio Gallonio, De SS. martyrvm crvciatibvs (Rome, 1594), 44. Leonardo’s monogram appears on page 123. See Giuseppe Finocchiaro, Cesare Baronio e la tipografia dell’oratorio (Florence, 2005), 86–89. See also Jetze Touber, Law, Medicine, and Engineering in the Cult of the Saints (Leiden, 2014), 222–230; Marco Pupillo, in La Regola e la fama: San Filippo Neri e L’arte (Milan, 1995), 513–514; Pupillo 2009, 840.

[28] Pupillo 2009, 837–840. A different woodcut image of Giove Pluvio appears in the 1590 edition of the Annales printed at the Tipografia Vaticana. Girolama’s version was used as a model for subsequent editions of the Annales, such as the one printed in Cologne by Anton Hierat and Johann Gymnich, without her monogram. For the double printing of the volume, see Finocchiaro 2005, 28–40.

[29] Cesare Baronio, Annales Ecclestiastici (Rome, 1594), 2:209. Finocchiaro 2005, 122: record of payment of eight scudi to Leonardo Parasole “per l’intaglio in legno di Giove Pluvio che va nel secondo tomo dell’Annali…”

[30] Thanks to Jamie Gabbarelli for alerting me to the Dente engraving.

[31] Impressions of The Last Judgment are in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Biblioteca Panizzi.

[32] Impressions of Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Art Institute of Chicago, and New York Public Library. The British Museum holds an impression dated 1623 published by Maurizio Bona, who also published posthumous editions of Isabella Parasole’s Teatro delle Nobili et Virtuose Donne.

[33] The largest sheet of paper, the foglio imperiale, was about 500 by 740 millimeters. The impression of Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs at the Art Institute of Chicago measures 415 by 672 millimeters. The next paper size, foglio reale, measured circa 445 by 615 millimeters.

[34] Pupillo 2009, 845: “Adi 8 [07.1622] morì la sig.ra Girolama Parasole scultrice, e pitrice…”

[35] The liturgical books included the Cerimoniale Episcoporum (Rome, 1600) and the Pontificale Romanum Clementis VIII… (Rome, 1595).

[36] Gabriele Paleotti, Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images, trans. William McCuaig (Los Angeles, 2012), 205.